By: Adam H. Rosenblum Esq. Published: 11/4/19

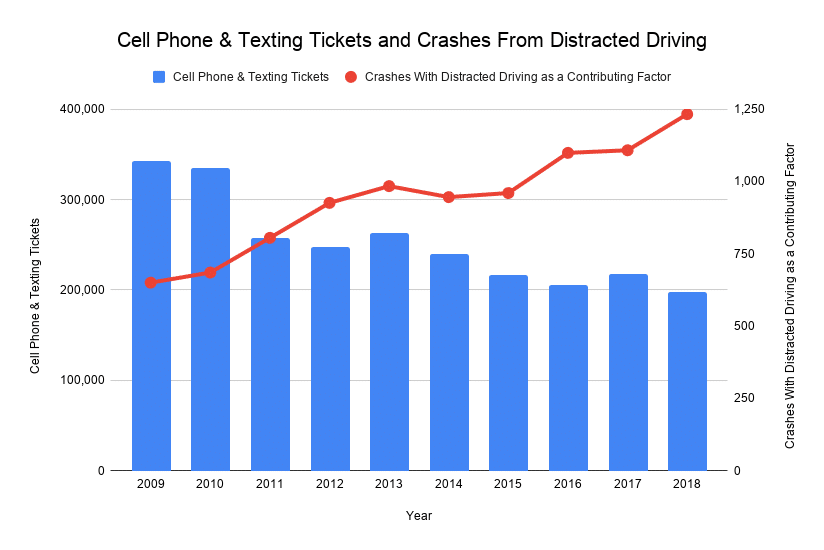

Over the past decade, government, law enforcement, and corporate have poured efforts into preventing accidents from drivers using their cell phones or texting behind the wheel. Unfortunately, 2018 data from the NYS Department of Motor Vehicles demonstrates that it had little effect.

In 2018, police across New York State wrote nearly 200,000 tickets to drivers who were talking on the phone without a hands-free device (cell phone ticket) or who were distracted by an electronic device used for calling, texting or apps, GPS, or other uses (referred to generally as “texting” in this article).

Despite the massive number of tickets written for these traffic violations, accidents related to cell phones and texting (and other electronic use) have been on the rise. The DMV breaks down crash data based on contributing factors, such as hand-held cell phone use, texting, other electronics usage, and navigation devices (i.e. GPS systems). In nearly all categories, the number of accidents that include such factors has risen significantly. In 2009, there were 650 such accidents. By 2018, that figure jumped 86% to 1,212; 924 were for cell phone-related crashes alone. The rate of injury and death in such crashes has remained more or less the same at about 50%. At the same time, after years of cell phone and texting tickets increasing dramatically year over year, 2018 marked the first time that the total number of both citations declined.

What Is Being Done to Prevent Cell Phone/Texting Crashes?

Much has been done throughout New York State (and nationwide) to attempt to reduce cell phone and texting-related accidents. The fine for a first offense was raised from $100 to $150, then again to $200. Points associated with a conviction increased from 3 to 5--on par with such offenses as reckless driving and failing to stop for a school bus. State agencies and law enforcement have also engaged in numerous public relations campaigns and enforcement initiatives. Gov. Andrew Cuomo has also made an effort over the years to rebrand many highway rest stops as "texting stops."

Automakers have also taken the issue seriously. But rather than convince people not to pick up the phone, they are making it less distracting to do so. Bluetooth connectivity has become increasingly common in most car models and is nearly ubiquitous. Other features, such as Ford’s SYNC operating system can read incoming texts aloud and send texts dictated by the driver. GM has been developing sensors and software that can detect when a driver’s eyes are no longer on the road--and even pull over if an auditory warning isn’t heeded.

After much controversy and a lawsuit, even Apple got on board and released a “Do Not Disturb While Driving” feature to its iOS operating system that disables all alerts while the vehicle is in motion.

Why Aren’t Anti-Texting Measures Working?

Despite technological advancements, informational campaigns and enforcement efforts, crashes related to cell phones and texting are on the rise. Traffic tickets, in particular, seem to have little effect, especially for texting. In 2009, only 181 tickets were issued for texting while driving (and using other electronic devices such as GPS systems) in NY. By 2017 that figure increased by several orders of magnitude to 112,529! And yet the number of associated crashes also spiked by more than 167%. Last year was the first year that the number of texting while driving tickets declined, slipping by 1.1% to 111,250.

One reason drivers can’t seem to put their phones down could be a matter of genuine addiction. Research shows that every time the phone “pings” with a text or app-related alert, it gives the brain a shot of dopamine. This stimulates the reward pathways of the brain--the same pathways associated with pleasure from eating, sex and alcohol. At the same time, when the brain feels rewards, science shows that the logic parts of the brain are blocked.

Another reason is that drivers are just generally more distracted, electronics or not. The number of serious crashes (those involving injury or death) associated with driver distraction--which could include anything from talking with a passenger, reading a billboard, or putting on mascara--has increased by almost 25% since 2009, from 23,750 to 29,608 in 2018. One author has suggested that people’s bad electronics habits are akin to bad eating habits.

It’s also worth looking at the follow-through associated with tickets. In 2018, approximately 30% of drivers were able to “plead down” a texting ticket by getting it reduced in court to a non-texting charge. The same is true of 38% of drivers that were hit with cell phone tickets. This begs the question as to whether the ability to get cell phone and texting tickets reduced has had a chilling effect.

What Else Can Be Done?

Short of rewiring the human brain, it seems like the battle to prevent cell phone and texting-related accidents is an uphill one. The problem is far from insignificant. Texting takes a driver’s eyes off the road for an average of five seconds; at 55 mph, this means traveling the length of an entire football field with one’s eyes closed. This is similar to the way alcohol affects reaction time behind the wheel. It makes sense, then, that the rate of injury and death would closely tack that of DWI-related crashes (54%).

That begs the question as to whether cell phone and texting violations should be treated the same as drunk driving. Prosecutors in Erie County have taken this approach in some cases and are seeking more aggressive penalties against distracted drivers. In 2018, the local district attorney convicted a truck driver for second-degree manslaughter following an accident that killed a University at Buffalo professor; he was sentenced to 4.5 years in prison. The driver, Kristofer M. Gregorek, was filling out an online customer satisfaction form for a new app on his cell phone at the time of the collision.

But a more recent incident involving an unlicensed driver distracted by her phone has not been subject to such aggressive prosecution. In September 2019, a Watertown woman caused a three-car crash in Oswego County that sent several people to the hospital. She was charged with a cell phone violation and two counts of aggravated unlicensed operation for driving while suspended, but prosecutors declined to file more serious charges.

In conclusion, the data shows that the problem of distracted driving caused by electronic devices appears to be getting worse, not better, despite numerous measures that have been taken to curb cell phone and texting behind the wheel. It would seem therefore that different approaches must be tried in order to try and address this serious concern.